Scalability remains a significant challenge in blockchain technology, prompting the exploration of innovative solutions like zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs). We explore the fundamental concepts of ZKPs and their application in addressing blockchain scalability, with a focus on zero-knowledge Ethereum Virtual Machines (zkEVMs). zkEVMs leverage ZKPs to enhance scalability in blockchain systems while maintaining a high level of security. We also provide a comparison of various zkEVM implementations, highlighting their differences and advantages. Specific attention is given to prominent open-source zkEVMs such as Polygon zkEVM and zkSync Era, detailing their technical stacks, zero-knowledge components, data availability solutions, and EVM compatibility. Performance benchmarks are also presented, comparing prover time, settlement costs, proof compression, and data availability costs.

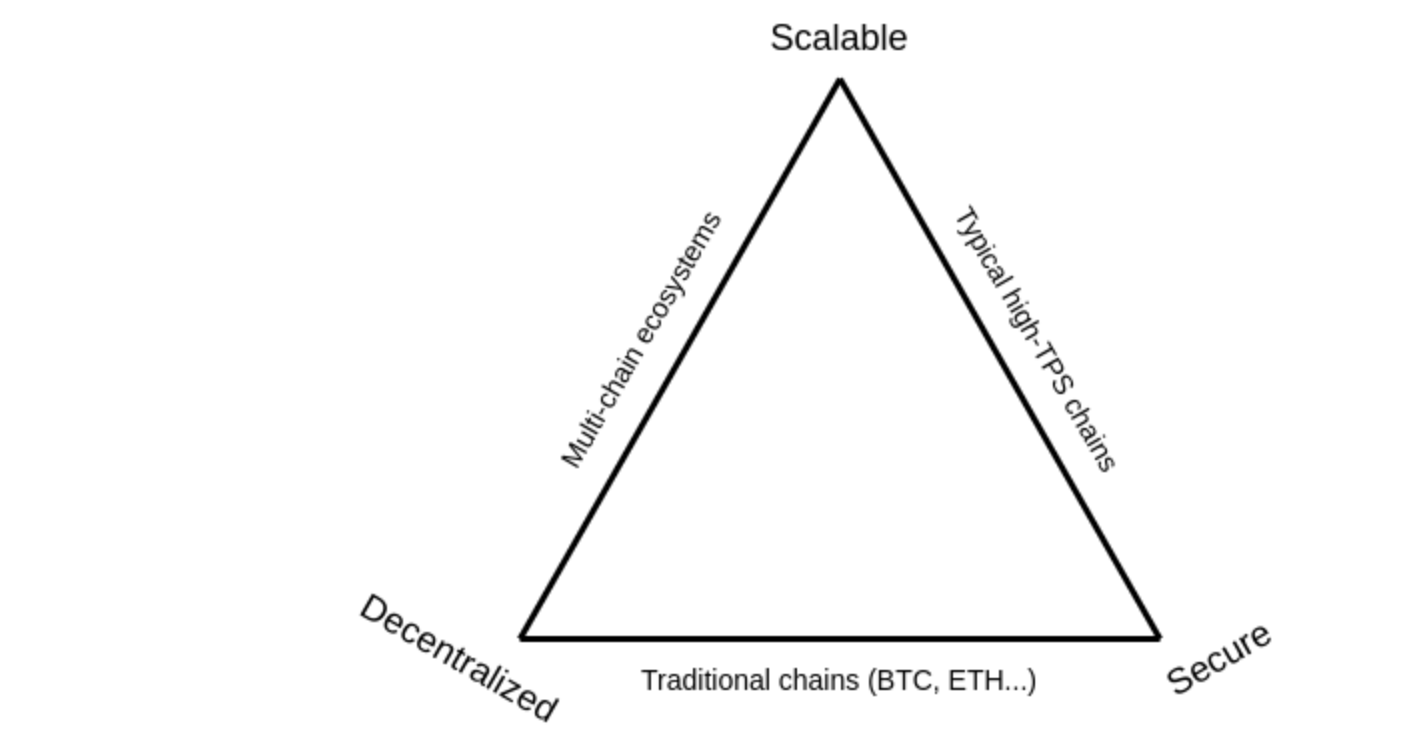

Blockchain trilemma

Blockchain trilemma (first coined by Vitalik Buterin) is a problem faced by blockchain engineers. The trilemma states that we cannot optimize all three aspects of a blockchain, namely, decentralization, security and scalability without accepting some kind of trade-off between them. Traditional blockchains like Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc are built upon security and decentralization. Therefore, they inevitably suffer from scalability problems. Recognizing this problem, the Ethereum team has proposed a rollup-centric roadmap to scale the blockchain through rollups.

Similar to how the Internet protocol is modelled as a multi-layer stack, a blockchain protocol can be divided into several layers.

- Layer 0 (L0): consists of hardware devices, protocols, connections, and other components that form the foundation of a blockchain ecosystem, Layer 0 acts as the infrastructure lying underneath the blockchain.

- Layer 1 (L1): carries out most of the tasks to maintain a blockchain network's fundamental operations like consensus mechanisms, dispute resolution, programming languages, policies, etc. This layer represents the actual blockchain.

- Layer 2 (L2): is an extra layer sitting on top of layer-1. Layer 2 performs the majority of transactional validations and heavy computations that are meant to run on layer 1. Layer 2 relies on layer 1 for security, so it frequently exchanges data with layer 1.

Scaling using rollups - layer 2

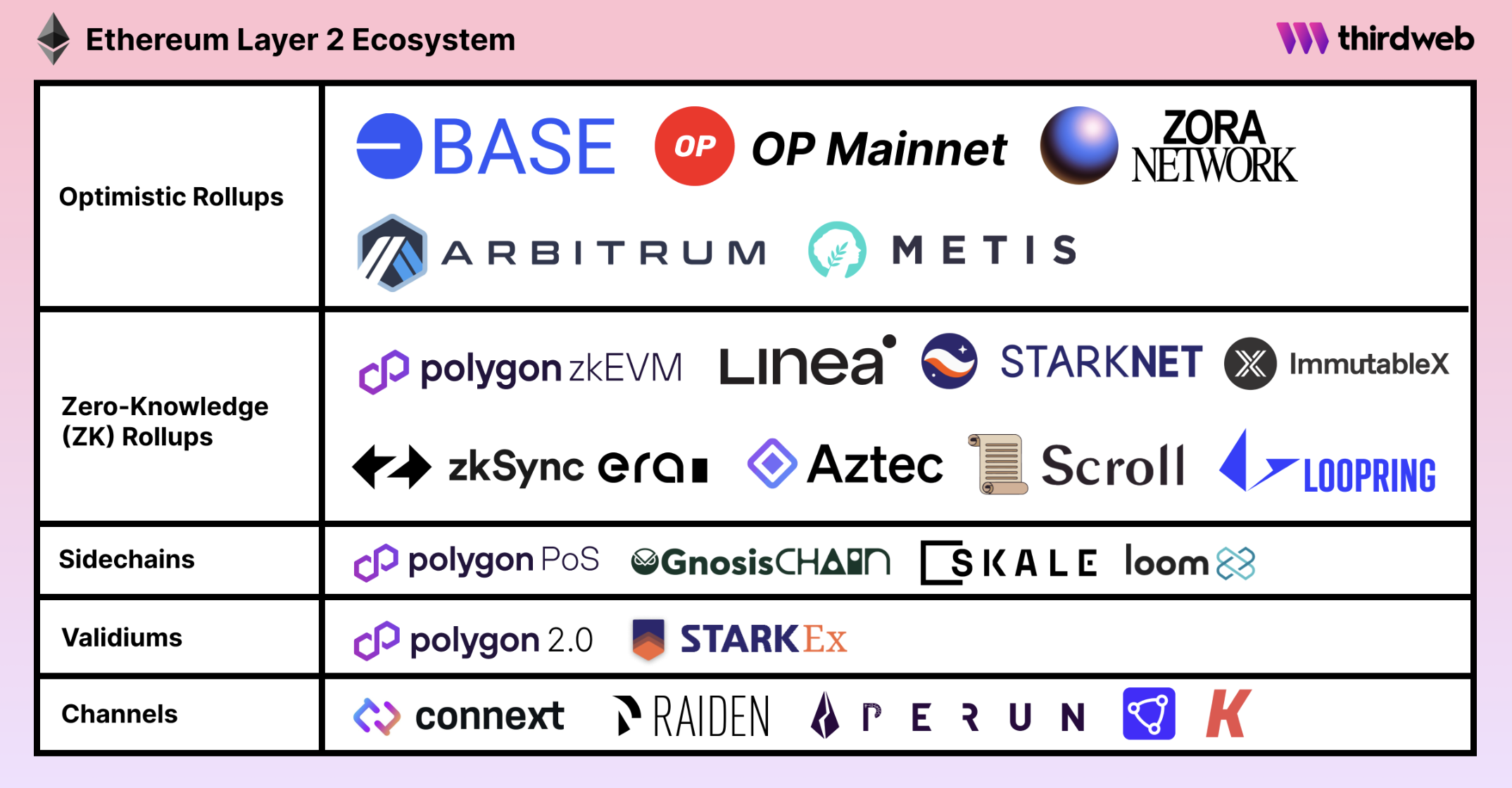

Scaling solutions refer to protocols that help solve the scalability problem of blockchain. A solution can be implemented on any layer of the blockchain, however, L0 and L1 are costly to modify as some changes might require a hard fork. Nowadays, the most widely adopted scaling solutions are implemented on L2 and many of them are rollups.

Rollup is a class of L2 scaling solutions that bundles several off-chain transactions into one on-chain commitment, hence reducing the overall cost of the protocol as fewer computations are performed on L1. According to how rollups enforce Computational Integrity (CI), there are two main types of rollups:

- In optimistic rollups, L2 sequencers submit batches of transactions to the mainnet without verifying their validity. Instead of immediate verification, optimistic rollups provide a challenge period, lasting up to approximately seven days, during which network participants can dispute the validity of any transaction.

- Zero-knowledge (ZK) rollups use advanced cryptographic techniques known as zero-knowledge proofs to validate transactions. This method allows the execution of transactions on L2 to be verified on L1 without a challenge period, significantly improving the user experience for cross-chain transactions between L1 and L2 compared to optimistic rollups.

In this article, we focus on ZK rollups (zkEVM). First, we present the concept of zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) and how ZKP can improve the scalability of blockchain. Then, we provide an overview of zkEVM. Finally, we summarize and compare some existing implementations of zkEVMs, evaluating their designs and performance.

What is zero-knowledge proof?

First devised in 1985 by Goldwasser, Micali, and Rackoff, an interactive proof system (IP) is an interactive protocol that involves two parties: a prover and a verifier. These two parties will communicate back and forth multiple times for prover to convince verifier that a statement is true. Any interactive proof has the two following properties:

- Completeness: If the statement is true, then an honest prover can convince the verifier with high probability.

- Soundness: If the statement is false, then, for any prover, the verifier rejects the proof with high probability.

If prover only sends one message to verifier, we say that the proof system they engaged in is non-interactive. One of the most employed cryptographic techniques to turn interactive proof systems into non-interactive protocols is Fiat-Shamir transformation.

In practice, the term "proof" is used interchangeably with "argument" and, most of the times, the latter is more accurate. Argument systems were introduced by Brassard, Chaum, and Crépeau in 1986. Compared to proof systems, the soundness property of argument systems is only required to hold against computationally bounded provers (provers with limited computing resources). According to this intuition, most modern computers are bounded, so arguments are considered "sound enough" in most cases.

A proof or argument system is considered zero-knowledge if the prover discloses nothing to the verifier other than the truthfulness of the statement being proved. With a zero-knowledge proof, a prover can prove that they know some hidden information. That secret information is, conceptually, a witness. In a zero-knowledge proof system, prover can perduade verifier that a statement holds while revealing any of the witnesses. One of the most well-known examples for zero-knowledge proof is the "Where's Waldo?" example. In this example, you want to convince your friend that you have found Waldo without disclosing his location in the picture. You can do so by using a board big enough to cover the entire picture when you show your friend the image of Waldo through a fixed peephole on that board. The witness, in this case, is the exact coordinates of Waldo.

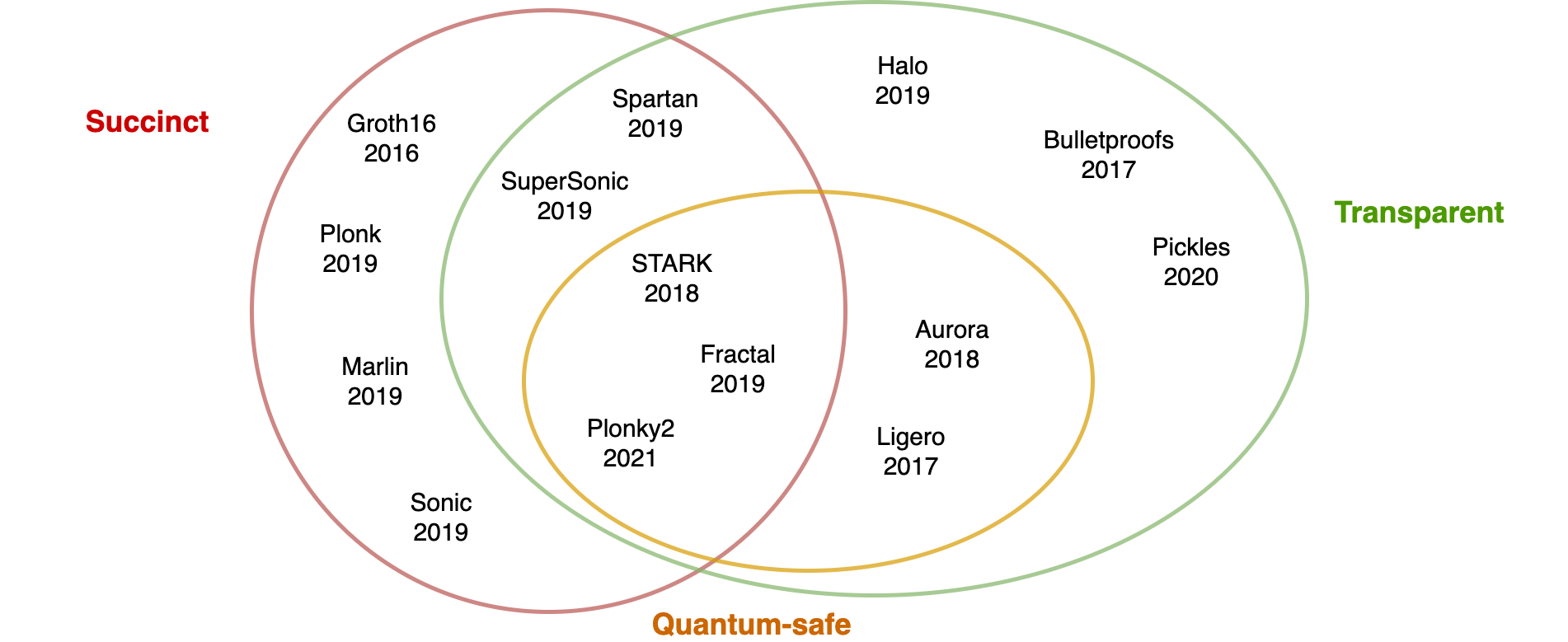

Currently, many practical zero-knowledge proof (or argument) systems have been realized. Most of these schemes fall into one of the two following categories:

- Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge (zk-SNARK):

- Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Arguments of Knowledge (zk-STARK):

The main difference between zk-SNARK and zk-STARK is the need for trusted setup - a piece of random data that must be honestly generated. In reality, randomness generation is not easy to implement securely, especially in a trustless setting (you can look at Zcash's counterfeiting vulnerability). Zk-STARK eliminates the need for trusted setup, which effectively reduces security risks and assumptions while increasing protocol's transparency. On the other hand, zk-STARKs usually have significantly larger proof size compared to that of zk-SNARKs. This can be a big problem if data transfer is expensive like in the case of Ethereum smart contracts. Therefore, elements of zk-SNARKs and zk-STARKs are sometimes combined in one protocol to get the best of both worlds, e.g., transparent zk-SNARKs like Plonky2 [7] and eSTARK [8].

Zero-knowledge proof is a fast-growing field of research and the race to practical and efficient general-purpose ZKPs is reaching new heights (a Cambrian explosion as described by Eli Ben-Sasson) with the rise of zero-knowledge Virtual Machines (zkVMs).

How do ZKPs improve scalability on blockchain?

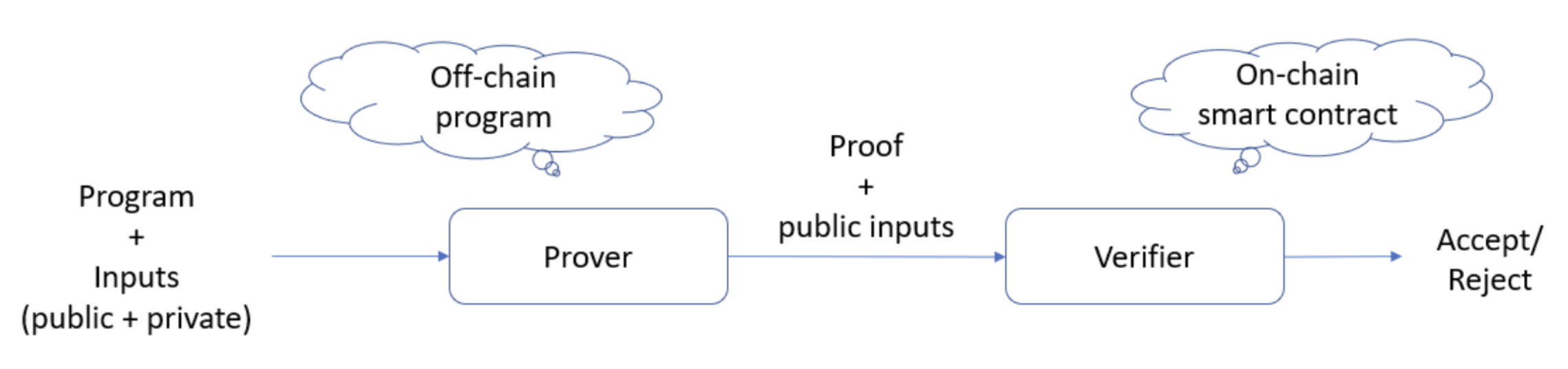

One of the most sought-after characteristics of zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) is succinctness — the capacity to substantiate a claim with a proof significantly smaller than witness. For instance, a prover can persuade a verifier that a computation has been correctly executed on a massive database (several gigabytes) without disclosing the entire database to the verifier. It is as though the prover has "compressed" the database into a concise proof (a few hundred bytes). Additionally, the verification of ZKPs is generally more cost-effective and faster than the naive approach of re-running the computation. With ZKPs, the execution of a vast number of transactions on L2 can be verified by a succinct proof submitted on L1 (see the figure bellow).

Since all transactions in L2 can be verify in L1, L2 can inherit the strong security of L2, even though the validators on L2 is compromised.

Zero-knowledge Ethereum Virtual Machine (zkEVM)

Overview

zkEVM is a virtual machine that executes smart contract transactions, providing compatibility with both zero-knowledge-proof computations and the EVM. EVM is quasi-Turing-complete (according to Ethereum Yellow Paper [9]), which means EVM can perform pretty much any computation that respects the bound set by gas. With the integration of ZKPs, the validity of any computation run on zkEVM can be verified. This allows us to "outsource" most of the transaction processing job from Ethereum to L2 via ZK rollup.

In essence, zkEVM can be described as asserting: "I have correctly executed the EVM with the provided inputs." However, this assertion needs to be formalized to be interpretable by the zero-knowledge component of zkEVM. This formalization process is analogous to how programmers must write code for computers to understand and perform a task. The formal representation required for this purpose is usually referred to as ZK circuits or arithmetic circuits.

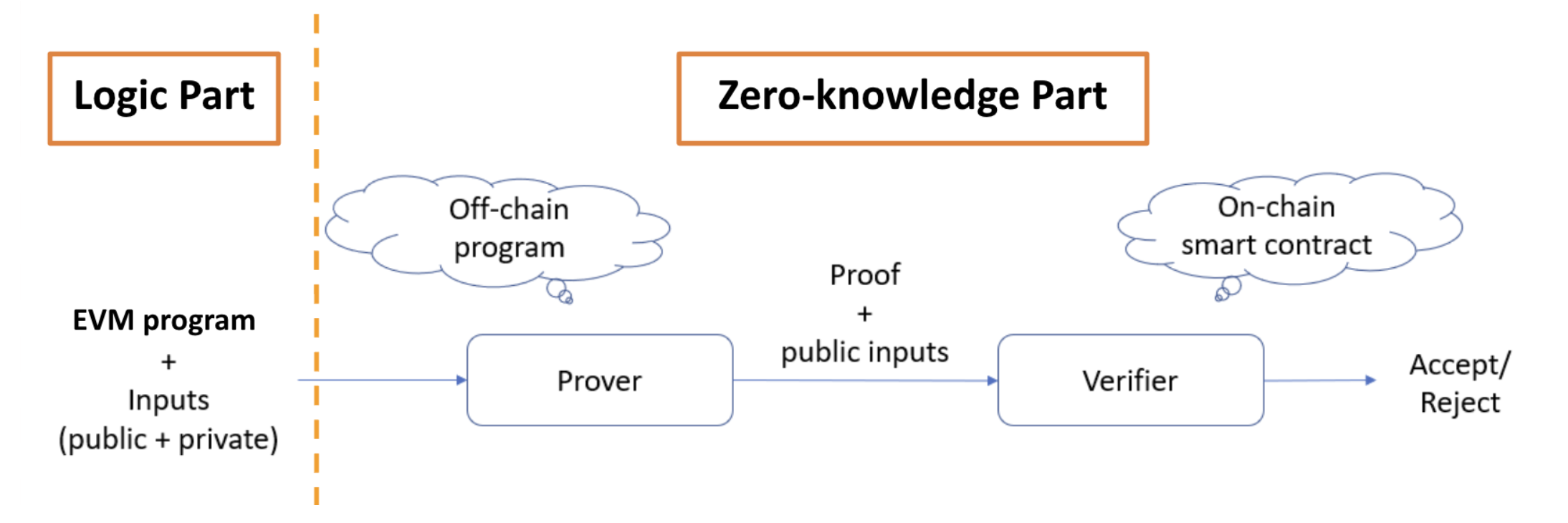

We can divide zkEVM into two parts:

- Logic Part:

- EVM program: EVM's logic expressed as ZK circuits

- Zero-knowledge Part:

- Prover: Off-chain program that generates proof given the EVM program and inputs

- Verifier: Smart contract that performs proof verification

Beyond logic and zero-knowledge aspects, ensuring data availability is critical. This guarantees users can access their transaction data, safeguarding their assets even in scenarios involving malicious activities.

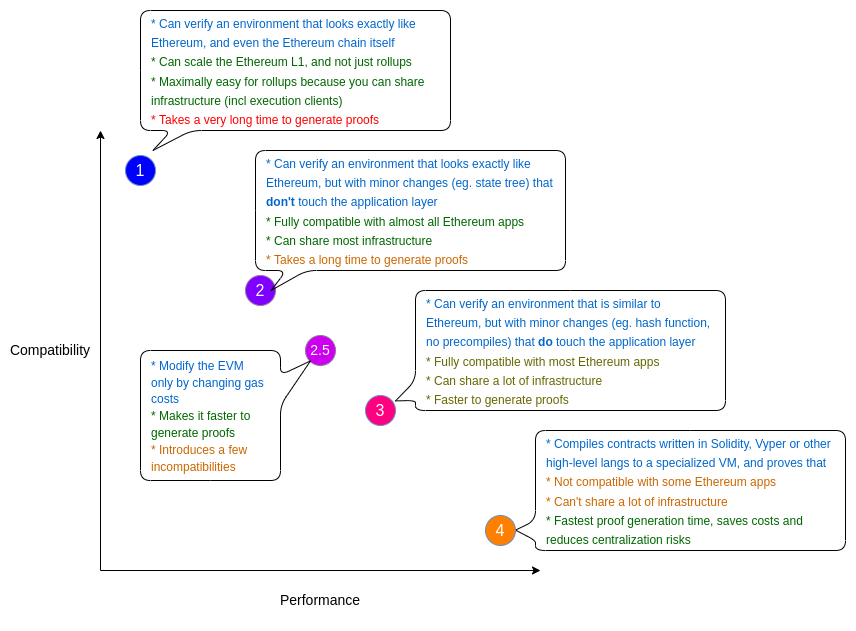

Another pivotal consideration is EVM compatibility. According to Vitalik Buterin, zkEVMs are categorized into four types based on their performance and compatibility with the EVM.

We are now examining two widely adopted and fully open-source zkEVMs: Polygon zkEVM and zkSync Era. We will begin by exploring the technical stack of each product, including their logical architecture, zero-knowledge components, and data availability (DA) solutions. Polygon zkEVM is primarily focused on optimizing fast proving times, aiming to expedite the verification process efficiently. In contrast, zkSync Era prioritizes data compression through its state diffs mechanism, which facilitates more economical on-chain settlement.

Furthermore, we will evaluate the EVM compatibility of both zkEVMs. Polygon zkEVM demonstrates high compatibility with EVM through its ability to directly interpret EVM bytecode without the need for an intermediate representation. On the other hand, zkSync Era's instruction set differs significantly from that of EVM, preventing it from directly interpreting EVM bytecode like Polygon zkEVM.

This comparison highlights the distinct approaches and technical considerations of each zkEVM in the context of their architecture, zero-knowledge features, data availability solutions, and compatibility with Ethereum's EVM. To quickly sum up what we have learnt in this section, below is a table that captures the key takeaways from our analysis of Polygon zkEVM and zkSync Era.

| Polygon zkEVM | zkSync Era | |

|---|---|---|

| EVM Compatibility | Type-2 zkEVM. It can directly interpret EVM bytecode | Type-4 zkEVM. Smart contracts must be compiled to EraVM bytecode to be executed |

| Proving time | Proving time remains constant regardless of input size | Proving time increases as input size grows |

| DA Solution | DA cost is significantly higher because of all transaction data is posted to L1 | DA cost is much lower as only (compressed) state differentials are published on L1 |

Polygon zkEVM

Polygon zkEVM is developed by Polygon Labs. Polygon Labs has open-sourced two implementations of their CPU prover (written in C++ and Javascript).

Logic Part: The logic part of Polygon zkEVM is divided into two parts: Polygon-VM and its ROM. Implementing logic part starts with a DSL called Polynomial Identity Language (PIL). This language is used to describe a uniprocessor VM. We refer to this machine as Polygon-VM. The firmware of Polygon-VM is written in a higher-level DSL called zero-knowledge Assembly (zkASM). The logic of EVM is contained within this firmware. Due to its immutability, the firmware is referred to as the read-only memory (ROM) of Polygon-VM.

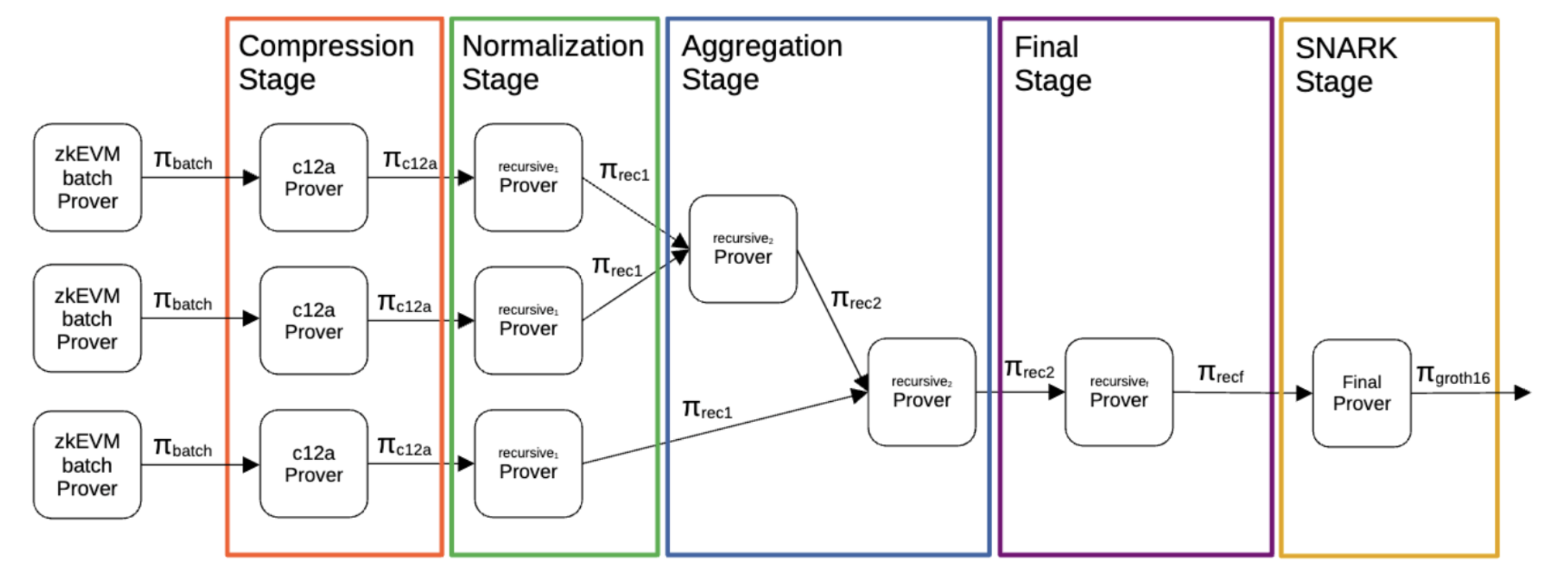

Zero-knowledge Part: Polygon zkEVM generates proofs of CI through a pipeline. In this pipeline, eSTARK [8] is utilized to perform proof recursion, aggregation and composition while Groth16 [1] or fflonk [10] is employed for proof compression. Because of the monolithic design of its ZK circuits, Polygon's prover is highly optimized to run on CPUs of a single powerful node.

DA Solution: All transaction data of Polygon zkEVM is stored on Ethereum smart contracts. More specifically, RLP-encoded L2 transactions must be saved to rollup contract for them to be processed. This approach is simple to implement, and gives maximum transparency.

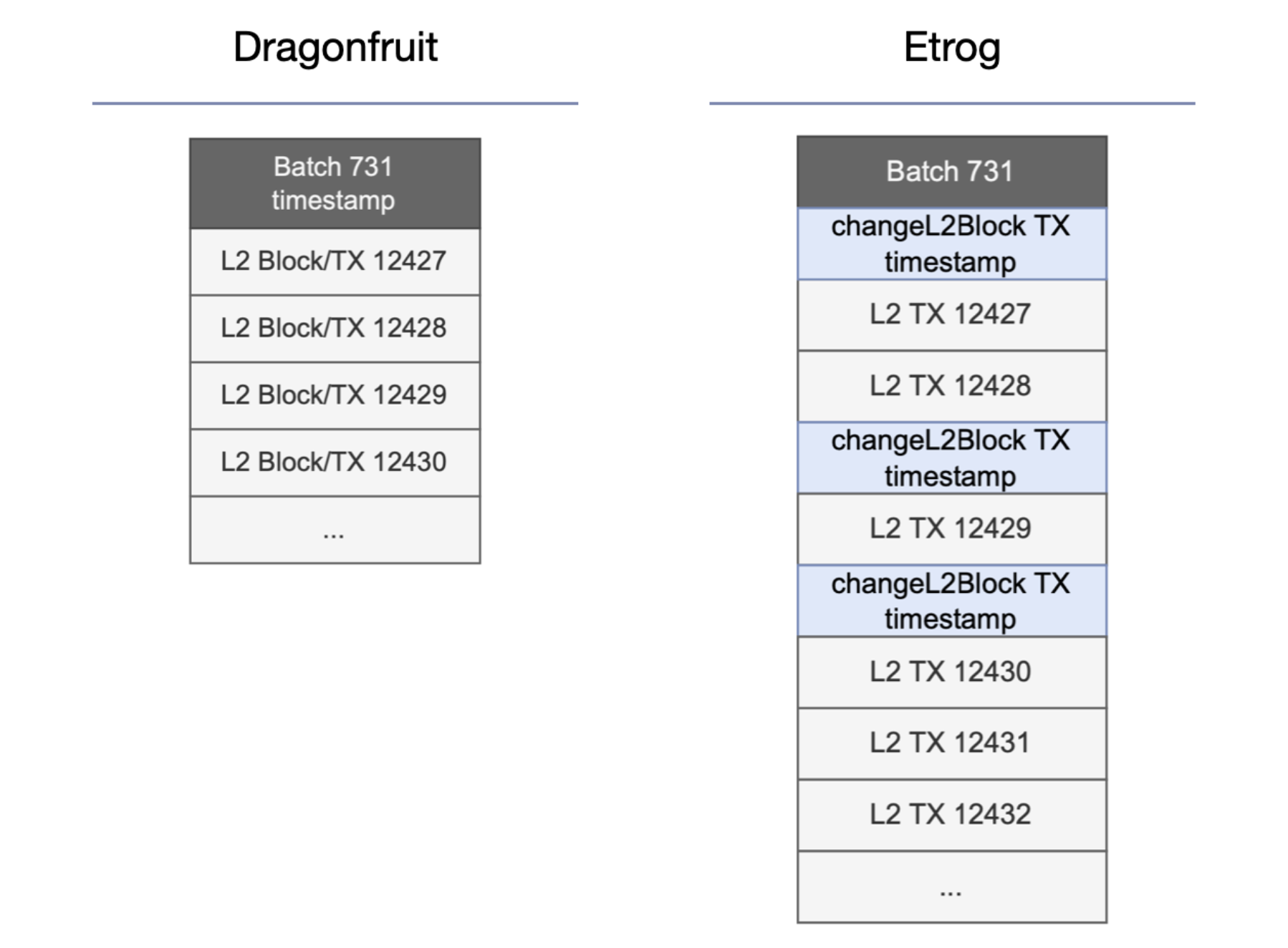

EVM Compatibility: Polygon zkEVM is nearly a full type-2 zkEVM, thanks to the Etrog update in early 2024. After Etrog update, dApps developers can redeploy their smart contracts exactly as they are on Ethereum without the need for additional auditing or modifications. As pointed out in Vitalik Buterin's blog, type-2 zkEVMs appear to be EVM-equivalent but they are, in fact, slightly different regarding some parts like block structure and state tree.

- Block structure: In Polygon zkEVM, multiple blocks (a.k.a. L2 blocks) are bundled into a batch. Unlike Ethereum blocks, Polygon zkEVM's L2 blocks do not contain any other data besides from the RLP-encoded transactions. A block consists of:

- Change-L2-block transactions: the deliminators for different blocks within the same batch

- Regular Ethereum transactions: at the time of writing, only legacy transactions are supported

- State tree: While the original EVM stores Ethereum's state in a Merkle-Patricia Trie constructed with Keccak256, Polygon zkEVM utilizes a Trie Binary Sparse Merkle Tree built with Poseidon-Goldilocks.

Polygon zkEVM's high compatibility with EVM is demonstrated by its ability to interpret EVM bytecode; no intermediate representation is required.

zkSync Era

zkSync Era is developed by Matter Labs. Matter Labs has open-sourced their CPU and GPU provers, namely era-boojum and era-shivini (both written in Rust).

Logic Part: Two main components of zkSync Era's logic part are Era virtual machine (EraVM) and system contracts. EraVM is a register-based VM written in Rust (based on the era-boojum library). Similar to modern operating systems, EraVM has a special feature called kernel mode in which privileged operations like calling system contracts are allowed. System contracts are smart contracts written in Solidity or Yul which can only be accessed by EraVM in kernel mode. Some logics of EVM are migrated to system contracts since it makes implementing native Account Abstraction (AA) easier. Moreover, writing smart contracts is much less of a hassle than building Rust ZK circuits.

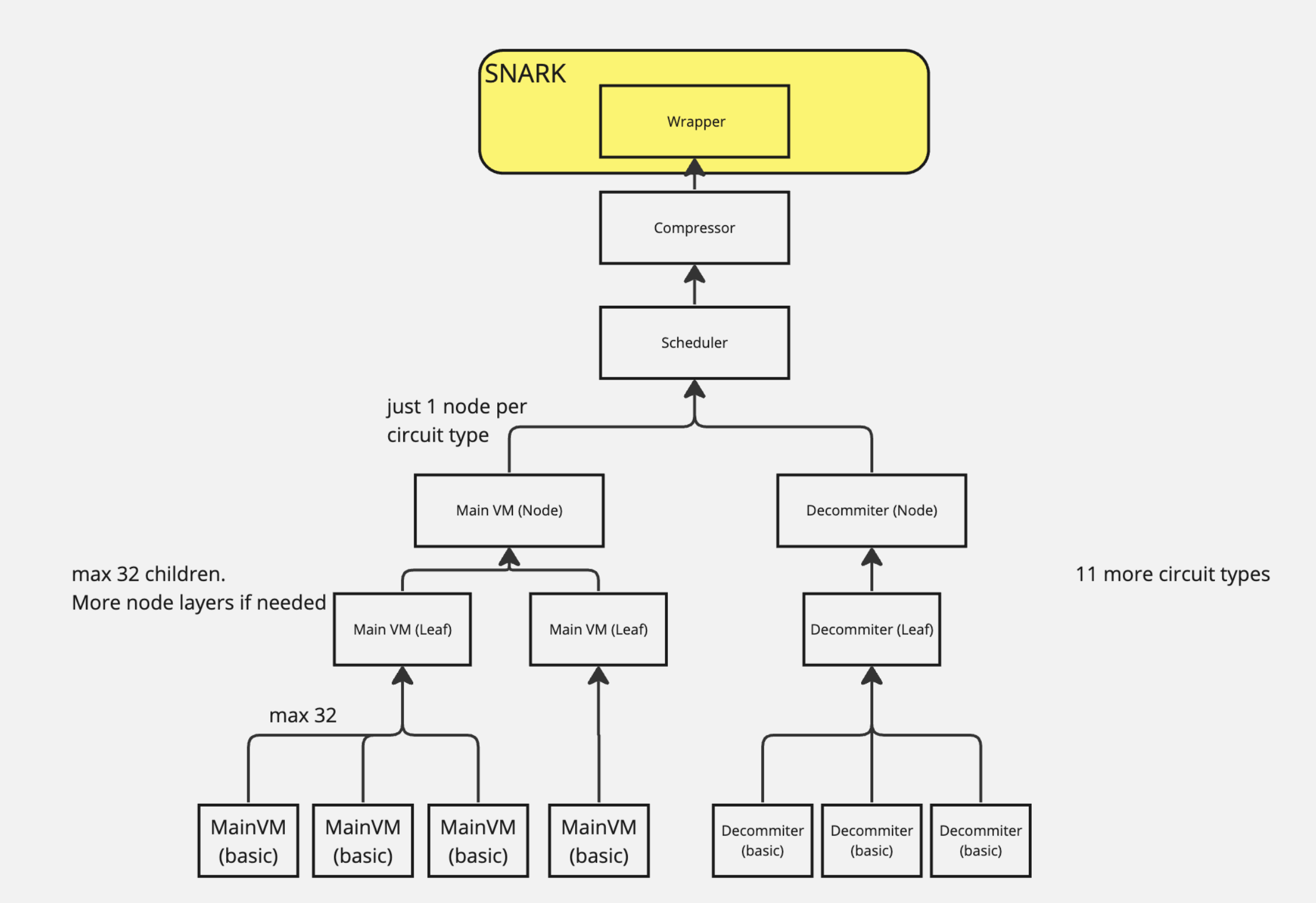

Zero-knowledge Part: zkSync Era uses a proof system called Boojum - an instantiation of RedShift [11]. A major source of inspiration for Boojum's design is Plonky2 - a transparent zk-SNARK tailored to fast recursive composition. In total, zkSync Era utilizes three types of ZK circuits: base-layer circuits, recursive-layer circuits and "AUX" circuits (see this document for more details). Overall, the proving architecture resembles a tree in which each node is a proof and every parent node is the aggregated proof of its children. Since the main ZK circuit of zkSync is divided into smaller circuits, zkSync Era's prover is able to scale horizontally as proof generation on base and recursive layers can be parallelized across a large cluster of CPUs or GPUs.

DA Solution: Instead of submitting detailed transaction data, zkSync focuses on posting state differentials ("state diffs") to L1. These diffs represent changes in the blockchain's state (account balance changes, storage updates, etc.), enabling zkSync to efficiently manage how data is stored and referenced:

- Efficient use of storage slots: Changes to the same storage slots across multiple transactions can be grouped, reducing the amount of data that needs to be sent to L1 and thereby lowering gas costs.

- Compression techniques: All data sent to L1, including state diffs, is compressed to further reduce costs.

EVM Compatibility: zkSync Era is classified as a type-4 zkEVM, which means compatibility is actively traded for faster development. To make comparison easier, we will examine the same aspects as we did for Polygon zkEVM.

- Block structure: In zkSync Era, there are two notions of blocks: L2 blocks and L1 batches.

- L2 blocks: blocks created on L2 (on the zkSync Era network). They are produced every few seconds, and not included on the Ethereum blockchain. An L2 block can contain a variety of transactions (legacy, EIP-2930, EIP-1559, EIP-712).

- L1 batches: batches of consecutive L2 blocks that contain all the transactions in the same order, from the first block to the last block in batch. As the name suggests, L1 batches are submitted to Ethereum.

- State tree: The state tree of zkSync Era is a single-level, full binary tree with 256-bit keys. Only changes of smart contract storage slots are written directly to state tree. The rest of Ethereum's state (account nonce, balance, code, etc) is managed by system contracts.

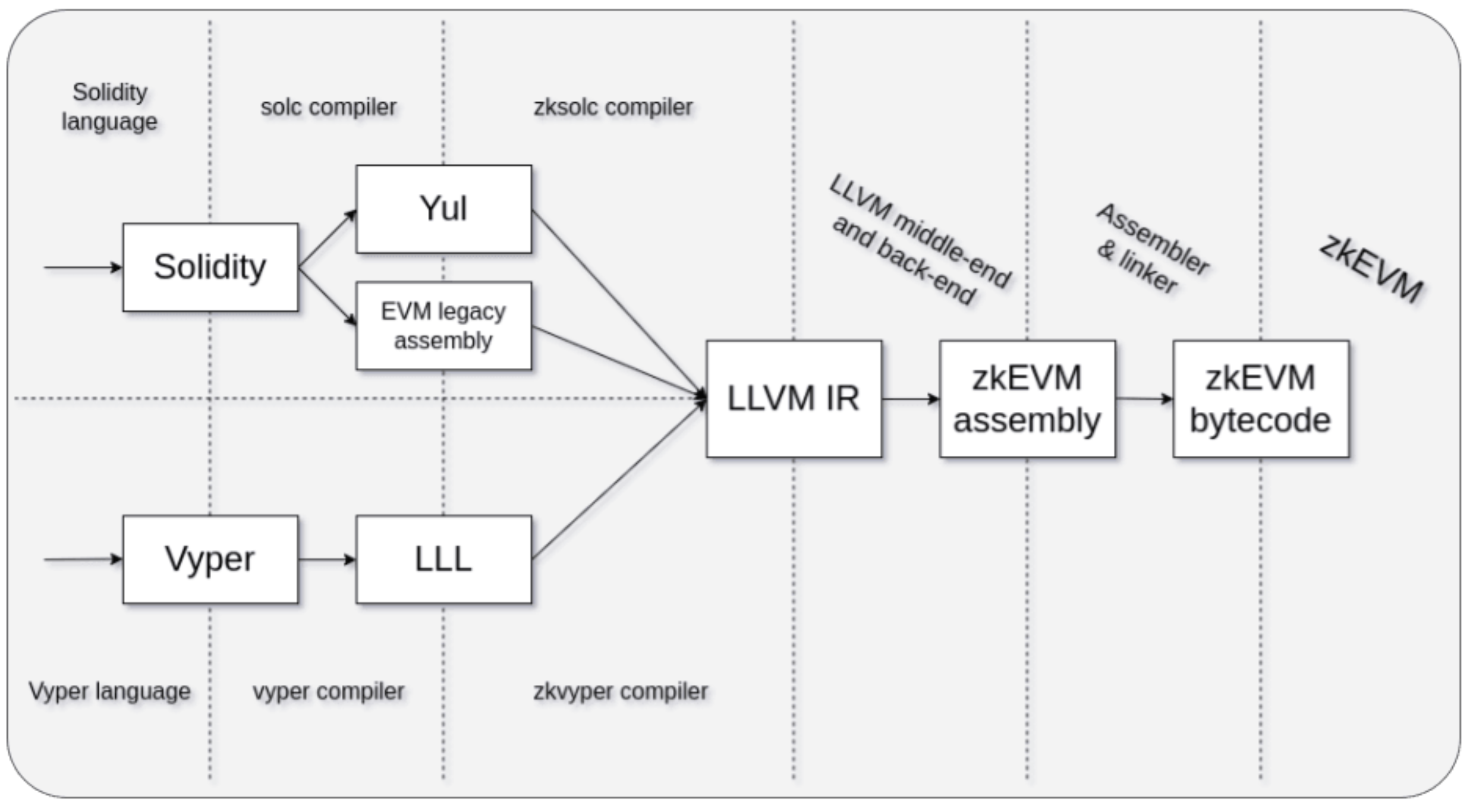

Since EraVM's instruction set is mostly different from that of EVM, it cannot interpret EVM bytecode directly like Polygon zkEVM. According to specification, EraVM only supports one native language called EraVM bytecode (a.k.a. zkEVM bytecode). In order to make this VM usable, the team at Matter Labs had to build a new toolkit for developers (zksolc/zkvyper for compilation, hardhat-zksync/foundry-zksync for debugging and testing). Compared to Polygon zkEVM, the compiler toolchain of zkSync Era is quite complicated.

Besides incompatibility at bytecode level, zkSync Era also deviates from EVM in many aspects such as fee model, computer architecture, built-in Account Abstraction, etc. Notably, some of these changes actually alter the behavior of execution layer.

Performance benchmarks

We summarize the benchmarks to compare Polygon zkEVM and zkSync Era based on data from [12]. In the benchmarks, the hardware to run Polygon zkEVM is an r6i.metal instance with 128 vCPUs and 1024GB of RAM, costing $8.06 per hour. For zkSync Era, the hardware is a g2-standard-32 instance with 32 vCPUs, one NVIDIA L4 GPU, and 128GB of RAM, costing $1.87 per hour.

Prover time. Polygon zkEVM maintains a proving time of either 190 or 200 seconds for each batch regardless of input size. In exchange for its outstandingly fast proof generation, Polygon zKEVM requires much more expensive hardware. On the other hand, the time spent on proof generation of zkSync Era extends with larger batch sizes. The proving time of zkSync Era increased from 400 to 1200 seconds when the batch size increased from 10 transactions to 200 transactions.

Settlement costs. The settlement costs take into account calling the L1 contract to commit to a specific batch, submitting proofs and executing the verifier logic (e.g., SNARK verifier) for the committed batches. The settlement costs per batch of Polygon zkEVM are cheaper. However, its batch size is smaller, resulting in higher settlement costs per transaction overall.

| Metrics | Polygon zkEVM | zkSync Era |

|---|---|---|

| Median Gas per Batch | 59,434 gas | 816,275 gas |

| Median Batch Size | 27 | 3,895 |

| Median Batch Size | 2,201 gas | 209 gas |

Proof Compression. The block's proof from one proof system to another can be compressed to a smaller proof. This typically involves proving the verification of the aggregated proof in a cheaper (with regards to the verification cost) proof system (e.g., Groth16) so that the cost of settlement is lower. For Polygon zkEVM, the median time of proof compression is 311 seconds while the number for zkSync Era is 1,075 seconds.

DA costs. One of the disadvantages of Polygon zkEVM is its high DA cost. The table below show the number of bytes used for DA for different payload types. The DA cost of Polygon zkEVM is 3-7 times higher than zkSync Era.

| Payload Type | Polygon zkEVM | zkSync Era |

|---|---|---|

| ERC-20 Transfers | 70,357 | 10,999 |

| Contract Deployment | 84,369 | 17,087 |

| ETH Transfer | 283,905 | 88,693 |

Based on the benchmarks, we observe that Polygon zkEVM and zkSync Era have distinct optimization focuses. Polygon zkEVM aims to optimize proving time, enabling faster synchronization between L1 and L2 chains. This allows cross-chain transactions to be executed more quickly. On the other hand, zkSync Era is optimized for settlement cost, focusing on minimizing the expenses associated with transaction settlement on L1.

References

[1] Groth, Jens. "On the size of pairing-based non-interactive arguments." Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2016: 35th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Vienna, Austria, May 8-12, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 35. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016.

[2] Gabizon, Ariel, Zachary J. Williamson, and Oana Ciobotaru. "Plonk: Permutations over lagrange-bases for oecumenical noninteractive arguments of knowledge." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2019).

[3] Bowe, Sean, Jack Grigg, and Daira Hopwood. "Recursive proof composition without a trusted setup." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2019).

[4] Chiesa, Alessandro, Dev Ojha, and Nicholas Spooner. "Fractal: Post-quantum and transparent recursive proofs from holography." Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2020: 39th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zagreb, Croatia, May 10–14, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 39. Springer International Publishing, 2020.

[5] Ben-Sasson, Eli, et al. "Aurora: Transparent succinct arguments for R1CS." Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2019: 38th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Darmstadt, Germany, May 19–23, 2019, Proceedings, Part I 38. Springer International Publishing, 2019.

[6] Ben-Sasson, Eli, et al. "Scalable, transparent, and post-quantum secure computational integrity." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2018).

[7] Polygon Zero Team et al. "Plonky2: Fast Recursive Arguments with PLONK and FRI"

[8] Masip-Ardevol, Héctor, et al. "eSTARK: Extending STARKs with Arguments." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2023).

[9] Wood, Gavin. "Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger." Ethereum project yellow paper 151.2014 (2014): 1-32.

[10] Gabizon, Ariel, and Zachary J. Williamson. "fflonK: a Fast-Fourier inspired verifier efficient version of PlonK." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2021).

[11] Kattis, Assimakis A., Konstantin Panarin, and Alexander Vlasov. "RedShift: transparent SNARKs from list polynomial commitments." Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2022.

[12] Chaliasos, Stefanos, et al. "Analyzing and Benchmarking ZK-Rollups." Cryptology ePrint Archive (2024).

Disclaimer

Please note that this content is presented or otherwise made available to you on an “as is” basis for general informational and educational purposes only, without representation or warranty of any kind. This content should not be construed or used as financial, legal, or other professional advice, nor is it intended to recommend the purchase or use of any specific product or service. You must seek your independent advice from appropriate professional advisors. Where this article is contributed by a third party, please note that those views expressed belong to the third party and do not necessarily reflect those of Sky Mavis. Please refer to our Terms of Service for more information.